| Coins | Emeralds | Silver Bars | Copper Ingots | Rapier Sword | Silverware |

Coins

The Spanish mint system, which produced this coin had its origin in great antiquity. In the Pre-Christian era coins were produced which resembled the Greek "drachma" with unmistakable inscriptions indicating their manufacture by citizens of the Iberian Peninsula, which comprises modern Spain. During the ensuing centuries, as Spain expanded its territories and power, its coinage became uniquely Spanish, reflecting the turbulent history and might of Spain. The Spanish Crown rigidly controlled the minting and issuance of this coinage. Old World mints in Barcelona, Seville, Madrid and other cities, were operated by the private sector under contract to the Spanish Crown.

The discovery and conquest of the New World uncovered a vast richness in precious metals and in 1535 a Royal Decree was issued establishing a mint in Mexico City. Later, mints were established throughout Central and South America, usually located near gold or silver mining areas.

Much of the bullion from the mints of the New World was sent to Spain in the form of coinage referred to as "cobs". Pieces of gold and silver of approximate size and weight were chopped from the ends of the flat bars of rough surface and irregular circumference of the blanks prevent well defined strikes. Consequently the legends are frequently missing or only partially visible. Coins of the 16th through early 18th centuries are rarely dated.

Gold coins are called "Escudos"; silver coins are called "Reales". During this period the coins were struck in denominations of 8, 4, 2, and 1 Escudos or Reales. The eight reale is known as a "piece of eight" and an eight escudo coin is the fabled "golden doubloon".

Emeralds

Atocha Emeralds were mined in the late 1500’s and early 1600’s. They are from the world’s greatest emerald mine. Muzo has consistently produced some of the world’s finest emeralds. Atocha Emeralds were recovered from one of the most famous treasure wrecks in history and are authenticated as genuine Atocha Emeralds only after “Adjudication of Ownership” by the Federal District Courts. Manuel Marcial de Gomar, an emerald expert in Key West recently said, “the Atocha Emeralds are the rarest in the world because they had to be found twice. Once in the original mining process and the second time by Mel Fisher in his historic discovery of the Atocha. Finding an emerald on the bottom of the ocean underneath ten feet of sand makes finding a needle in a haystack an easy job.”

Silver Bars

Approximately one thousand silver bars weighing between sixty and seventy pounds were listed on the Atocha's manifest when it sank. The majority of the ingots were the property of individuals, although one hundred thirty-three bars, shipped in thirty-four boxes and marked with a red crown belonged to King Philip IV himself.

Many Atocha silver bars were mined and processed in Potosi, now in present day Bolivia, and hauled great distances to Portobello, a Caribbean port in what is now the Republic of Panama. The cargo was then loaded onto the Atocha; each item registered as it was brought aboard. During processing, each bar was struck with a serial number and various monograms indicating the owner or shipper. The mint's assayer would then remove his "bite", a small piece that was tested to determine the purity of silver. Once purity was established, the ingot was struck with the "Ley" or fineness number, typically 2380 out of a possible 2400 or 99.2% pure. All bars not belonging to the king were also struck with one or more tax stamps indicating the 20% royal tax "Quinto" was collected. Some bars were dated.

Each bar was graded and assigned a class factor rating ranging from .5 to 1.0. The very best bars received a 1.0 rating and are characterized as being listed on the ships manifest and having a clear fineness mark, talley number, and at least a partial date. Class factor .9 bars are similar, but usually lack a date or have weaker markings. 0.8 bars are weaker yet, are almost always undated, but can still be traced to the manifest. 0.7 bars have at least two marks, but not of sufficient quality to trace the bar to the ships manifest. 0.6 bars have only light traces of marks and .5 bars have no marks at all.

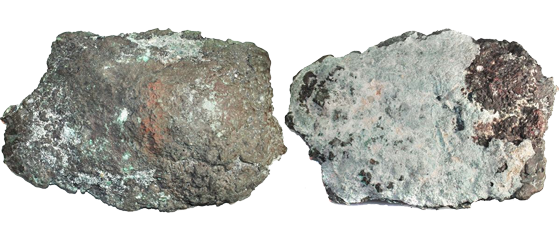

Copper Ingots

Five hundred and eighty-two copper ingots were loaded onboard at Havana, the Atocha’s final stop in the Indies before sailing to Spain. The copper originated from the mine at Caridad del Cobre in the extreme southeast of Cuba. The mine was owned by the crown, and operated by a factor, Juan de Eguiluz. The miners who worked these deposits were slaves of African origin, and, because of this, Eguiluz was a man who also had a hand in the slave trade. After the ore was refined, the copper was cast into crude ingots, transported to Santiago de Cuba and then shipped in fregatas to Havana. Eguiluz turned it over to Crown officials at that port city, and it was then loaded onto the guard galleons of the fleet.

Though these ingots are crudely cast, seemingly from simple depressions in the ground, three basic forms have been discerned; rectangular, oval, and an elongated, “boat” shape. All the ingots have highly irregular, bumpy surfaces. None bear markings of any sort. The contemporary records of the Atocha’s lading refer to these ingots simply as planchas, with no differentiation for form or size.

Rapier Sword

The word "rapier" generally refers to a relatively long-bladed sword characterized by a complex hilt which is constructed to provide protection for the hand wielding it. Its development began at a time period when the need for a lighter and faster sword became mandatory thanks to the introduction of firearm use in warfare. Early fencing and dueling techniques were developed as an effective measure for one handed "cut and thrust" combat. The few swords recovered from the Atocha wreck were constructed of famous Toledo steel and today are considered very rare.

Silverwares and Plates

In the 15th and 16th centuries, silver dinnerware graced the tables of the affluent. Since then, the art of silversmithing has been gauged by the quality of the dinnerware popular at any given time. The silver dinnerware found on early shipwrecks in the Americas was made by some of the finest European craftsmen of the time. Spaniards delighted in an ostentatious display of wealth. This was apparent through the way in which clothing and weapons were decorated, and also in the use of silver and gold objects for everyday purpose. The pieces on the 1622 Spanish galleons are prime examples of the rich tradition of silversmithing.

Private Collection